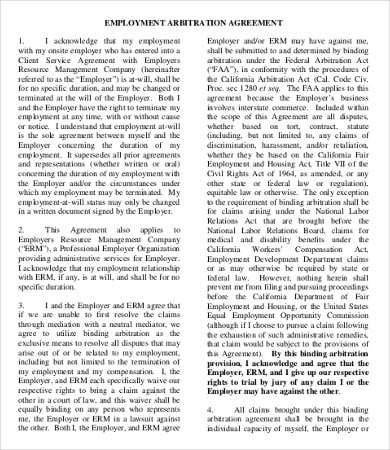

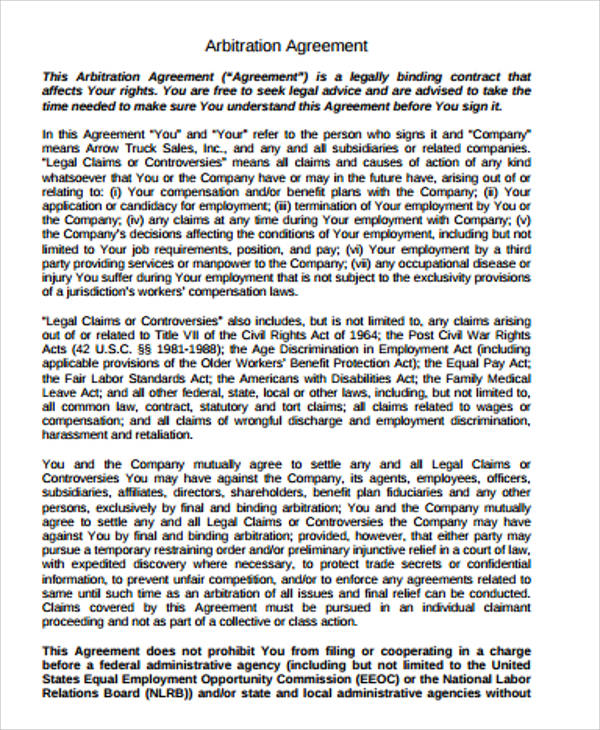

This article will discuss the Supreme Court's 2002 landmark decision regarding the role of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission ("EEOC") in relation to private arbitration agreements and the evolving views of California courts on the enforceability of such agreements, and will discuss some of the provisions that will make for fair, equitable, and enforceable arbitration agreements.An arbitration agreement is a contract in which you and your employer agree that certain disputes will be decided in arbitration, not litigation. While arbitration is now widely embraced as an effective alternative dispute mechanism, courts still require arbitration agreements covering statutory employment claims to be substantively and procedurally fair and conscionable to be enforceable. The year 2002 ushered in significant developments in the legal landscape in this area.

§ 1 et seq., written agreements to arbitrate generally are valid except when contained in "contracts of employment of seaman, railroad employees, or any other class of workers engaged in … interstate commerce." In its landmark 2001 decision in Circuit City Stores, Inc. Waffle House : Supreme Court Affirms EEOC's RightsUnder the Federal Arbitration Act ("FAA"), 9 U.S.C. As they are prepared after the dispute has arisen, they tend.EEOC v. If you have claims against your employer that are covered by the agreement, you must take them to arbitration instead.What is a Submission Agreement A submission agreement is less common than an arbitration clause.

The Court noted that the EEOC is specifically empowered by various statutes, such as Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Age Discrimination in Employment Act, to bring suit in federal court and to seek injunctive relief, reinstatement, backpay, compensatory damages, and punitive damages. When the EEOC filed suit against Waffle House in federal court, Waffle House argued that its arbitration agreement with the employee precluded the EEOC from proceeding to court for damages on the employee's behalf.The Supreme Court ruled that an arbitration agreement between an employee and an employer cannot eliminate the right of the EEOC, a non-party to the agreement, to sue for the types of relief it otherwise would be able to pursue. 279 (2002), the Supreme Court answered this question in the affirmative, confirming the EEOC's right to bring such a lawsuit.In Waffle House, the employee agreed that "any dispute or claim concerning his employment would be settled by binding arbitration." The employee subsequently was fired and filed a charge of discrimination with the EEOC. Waffle House, Inc., 534 U.S.

Luce, Forward, Hamilton, & Scripps, 303 F.3d 994 (9 th Cir. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit (which includes California and eight other Western states) was the only federal appeals court to refuse to enforce agreements to arbitrate employment discrimination claims. Given these statistics, the Waffle House decision should not deter employers from entering into arbitration agreements with employees.The Shifting Arbitration Landscape In CaliforniaUntil September 2002, the U.S. For example, in the fiscal year 2001, the EEOC received 80,840 charges of discrimination, and filed only 385 lawsuits (including cases filed by private individuals in which the EEOC intervened on the plaintiff's behalf). Thus, the EEOC was permitted to sue Waffle House on the employee's behalf.Although the Waffle House decision may seem to undermine the purpose of arbitration agreements between employers and employees, the practical effect of this decision is limited, as the EEOC actually sues employers very infrequently.

States have different standards for determining unconscionability, and there are no bright-line rules rather, employers must consider the locale of their workforce and the applicable standards of each jurisdiction when drafting such agreements and tailor them accordingly. See Ferguson, 298 F.3d at 778 Brennan, 198 F. The "procedural" requirement is typically met unless there is an element of unfair surprise or trickery in one or more of the agreement's provisions, or one of the parties lacked a "meaningful choice" in deciding whether to sign the contract. Bally Total Fitness, 198 F. Countrywide Credit Industries, Inc., 298 F.3d 778 (9 th Cir. However, various courts have warned that arbitration agreements must comply "with the principles of traditional contract law, including the doctrine of unconscionability" and must meet "procedural" and "substantive" due process requirements to be enforceable.An arbitration agreement will generally meet the "substantive" requirement unless an element of the agreement is unfair, oppressive, or unreasonably favorable to the party against whom unconscionability is claimed.

The scope of the agreement was unfairly one-sided because it exempted from arbitration those claims likely to be pursued by the employer (such as claims based on the employee's alleged misappropriation of trade secrets or confidential information), but required all claims brought by the employee to be arbitrated. The court also examined the scope of the agreement, its fee provisions, and its discovery provisions, and found the agreement substantively unconscionable. Initially, the court determined that the agreement was procedurally unconscionable because of the parties' unequal bargaining power and because the terms of the arbitration agreement were presented to the employee as a non-negotiable "take it or leave it" proposition. The court found that the agreement at issue in Ferguson contained several offensive provisions. Foundation Health Psychcare Services, Inc., 6 P.3d 669 (Cal. In Ferguson, 298 F.3d at 778, the Ninth Circuit examined the validity of an arbitration agreement in light of California's conscionability standards set forth in Armendariz v.

Supp.2d at 377 (agreement found unconscionable due to variety of factors, including (i) inequality in bargaining positions (ii) inadequate time for employee to review arbitration agreement (iii) employer's threats regarding job security to employee refusing to sign the agreement (iv) employer's failure to advise employee of her right to have an attorney review the agreement (v) employer's failure to inform employee of the agreement's impact on complaints against employer and (vi) employer's high pressure tactics to coerce employee's acceptance of onerous arbitration agreement). Rptr.2d 671 (2002) (employment arbitration agreement was unenforceable because it was "unfairly one-sided" because it required "arbitration of most claims of interest to employees but exempt from arbitration most claims of interest to " and because of the employer's threats to employee) Brennan, 198 F. Lastly, the Ninth Circuit found that various restrictive provisions of the agreement, such as one limiting the scope of the employee's discovery, reflected an overall "insidious pattern" favoring the employer.Because the agreement was "so permeated with unconscionable clauses," the court concluded that the offending provisions could not be severed from the agreement, and that the agreement as a whole was therefore unenforceable.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)